Methodology

Modus Operandi

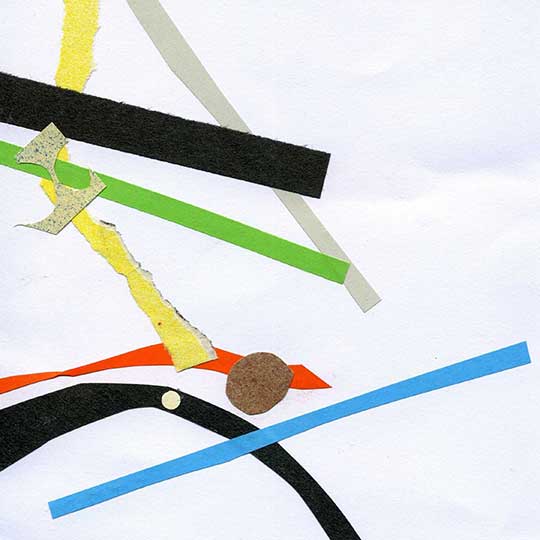

How a work begins is a matter of 'order', not chance. The artist decides on the particular context - sort of materials, or colours, perhaps, as well as which given set of protocols are to be applied.

Then 'chance' takes over. The process follows a sequence of 'actions' or 'events'. The throw of a dice determine which of a set of six alternative actions are to be followed. For instance, 'surface applications', where the dice is used to decide what medium, - paint, say - which colour, type, and what method of application - brush or spray, for instance. The location if the action is also decided by chance using a grid reference system.

As well as actions involving the application of coatings like paint, the dice can identify other actions involving adding, or subtracting materials, arranging or rearranging, or even destroying or degrading areas.

The arbitrary choice and application of actions - often very many - more than fifty, say - continues, often over a long period of time - until the artist calls a halt. Like the opening context for each work, this a matter of the artist's decision - of 'order' not chance.

The works are usually framed as 'objects' rather than pictures - as physical entities - within two sheets of glass or perspex, in much the same way as a specimen is mounted for microscopic examination.

Art Trail 2015 Press Release

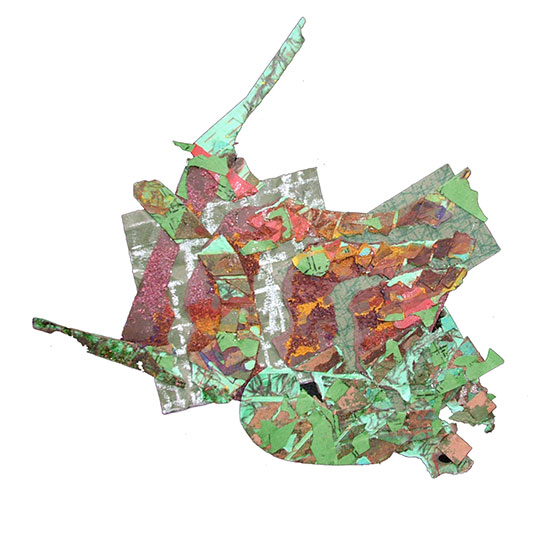

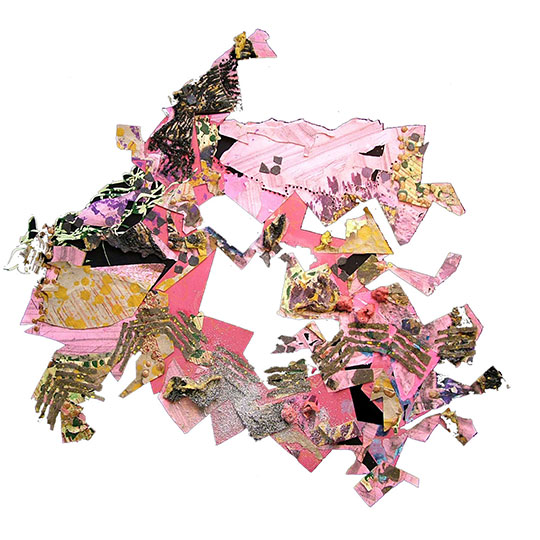

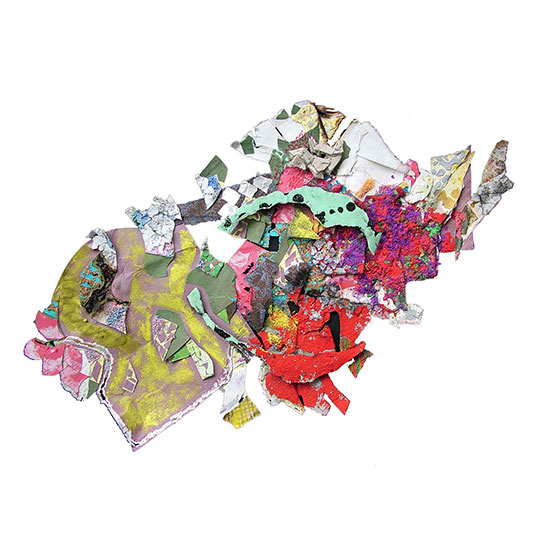

Made by throwing a dice, Daniel Dahl’s landscape analogues refer to, but do not represent, what we see. These abstract collages reflect his interest in notions concerning evolution, emergence, and complexity. It is argued that non-linear, dynamical systems arise ‘bottom up’ from multiple interactions between many simple elements, rather than ‘top down’ via pre-determined designs or prescritions.

To produce works in response to these ideas, Dahl uses processes involving chance and order. Random choices from comprehensive lists of every potential action, material, and compositional arrangements involved in making abstract collages, (order) are made by throwing a dice (chance). One decision (to spray red paint at coordinates1:5 , for instance) will be one of many others in what are often long sequences of separate actions.

Maybe the question then is, if viewers find any of the results pleasing, how can that be, given they are the product, not of artistic judgement, but of chance? Come to that, why might a particular landscape, say, itself the product of an the random interaction of many given elements, be found to be pleasing?

Aleatory Art Works 1994 – 2012

Considering Landscape Analogues: Questions Rather Than Answers?

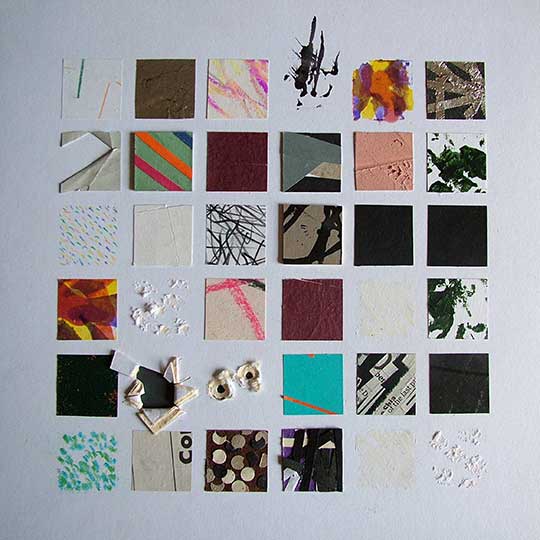

At first glance, these "Chance + Order: Landscape Analogues" works look like fairly straightforward abstract collages, that is, glued arrangements of torn or cut paper or card, or wood, plus a variety of media or treatments and techniques, including paint, ink, chalk - in fact, all the usual art applications. In addition, there is sometimes evidence of burning, rubbing and other physical actions.

Apart from a slightly 'unfinished' quality, with some fairly uncompromising 'rough-at-the-edges' passages, it is possible to approach these works in much the same way as other similar abstract art works. The juxtaposition of colours, shapes and textures may be found aesthetically pleasing, making appear it appear that the artist’s intention is to produce something beautiful.

However, the works are made using chance. The label includes ‘aleatory’, that is, determined by the throw of a dice. This may well raise some awkward questions, especially if the works are found to be aesthetically attractive. How can such a quality arise from a series of accidents? And then there is their relationship to landscape, some examples of which are designated ‘beautiful’ and “worth a detour”. What combination of qualities prompt some people to see one passage of countryside (or townscape) as allegedly being more attractive than others? Is the response to ‘beauty’ ‘natural’ – some sort of biologically innate empathy, or conditioned, the cultural product of history and convention?

The fact remains that these aleatory collages are produced using chance. They are not designed. Significant effort has been made to avoid applying the usual aesthetic judgement. However, although the works are made using chance, they are not arbitrary. They are designated “chance and order”, meaning they are not just a matter of accident. 'Order' refers to the artist’s pre-determined lists of all the possible actions, means, materials and techniques that might be utilised in making the work. The throw of a dice, the spin of a wheel, or some other ‘chance operation’, decides which of these are applied, when, how, and in what combination or sequence. ‘Order’ also includes both the opening context (which set of protocols or which particular materials) and the decision about when a work is finished.

Why this procedure? From a simplistic point of view, because the artist likes the results, the way the works discover themselves, arising from nothing more than the processes involved in their own production. In that sense, the works are not composed, but 'emergent', the result of sequences of autonomous actions and events interacting with each other - bottom-up - rather than from a centralised composition or design - top down. The works evolve from the random interplay of processes, methods and materials rather than from design or calculation.

Although the works are made using chance, they are not arbitrary. They are designated “chance and order”, meaning they are not just a matter of accident.

Chance + Order Series: A Reaction

to Mathematics, Science?

Part of the motivation behind these aleatory collages is the artist’s interest in the scientific and mathematical theories concerning dynamical systems theory, complexity and emergence. These notions suggest that life arises 'bottom-up' from many simple components interacting simultaneously, rather than 'top-down' via predetermined designs. Whilst this involves accident and happenstance, it is not arbitrary, but a combination of chance and order, "a kind of deep, inner creativity that is woven into the very fabric of nature."

Many other artists’ work can be seen as a reaction or response to new developments in science or mathematics. Constable, who attended lectures on the developing science of meteorology, suggested landscape painting could therefore be seen in a new light:-

"Painting is a science, and should be pursued as an inquiry into the laws of nature. Why, then, may not landscape be considered as a branch of natural philosophy, of which pictures are but the experiments?"

And at the beginning of the C20th, artists reacted to the development of startlingly different scientific and mathematical theories. They found the existing conventions of art and sculpture lacking, finding it necessary to develop new forms of practice to suit the new thinking.

For instance, Duchamp’s representation of a reality which would be possible by slightly distending the laws of physics and chemistry was based not on the Euclidian, three-dimensional concept of space but rather on the new four-dimensional and non-Euclidian concepts that were among the most talked about questions of modern scientific thought in the circles of avant-garde artists around 1910. In the same way that modern mathematicians no longer limited their thinking to the previous geometry, the cubist painters felt they needed to invent new visual forms of expression to match the new possible dimensions of space.

Duchamp (who also used chance in his work) originated the notion of the work of art as a 'brain-fact' ('cervellite'), supported by a structure of concepts rather than by the material apparatus of canvas and wood. If this divergence is related to the use of systems, then it will be apparent that the implication of early Cubism is to explore the suggestive notion of painting as its own system.

Picasso, too, was aware of, and intrigued by, contemporary developments in science and mathematics, evolving a new way of painting appropriate to what he felt was a different way of regarding reality. The appearance of new concepts appeared to offer artists an avenue away from conventional representation.

Such art is not intended to just illustrate science or mathematics. The work of the artist differs from that of the scientist and philosopher in that it proceeds in an entirely opposite direction and develops the ability to transform concepts into “perceptual metaphors,” which are “individual and without equals” and thus render it impossible for criticism to derive new laws, axioms, and “clearly marked boundaries” from them.

Thus, Mondrian’s aim was to reveal the essentials of reality by means which are independent of allusion to nature; by relationships, which are universal, rather than by forms, which are particular. Keith Tyson has talked about his art being “manifestations” as opposed to representations, or pictures of reality.

Such art operates parallel to, but not coexistent with, science. The artists are not making science (though it has been said that Duchamp developed the concept of art as an experiment, a concept according to which painting was no longer either an “open window” – a representation of a perceived or imagined reality – or an autonomous reality in its own right, but a pseudo-experiemental method that was at once an image and an instrument.)

The studio is not the science lab.: the two operate in different contexts. In the one, scientists and mathematicians develop, test and prove theories that can transform our perception of how the world works. In the other - the cultural context – artists’ work provides opportunities for people to contemplate their feelings about such theories and their implication. The reception of science is different from the reception of art, but both carry on human’s perpetual struggle to make sense of ourselves and our reality.

The reception of science is different from the reception of art, but both carry on human’s perpetual struggle to make sense of ourselves and our reality.

Frames of Reference

The ‘Chance + Order’ series are influenced by notions from complexity, emergence and dynamical systems theory. Such ideas can also offer another way of analysing artists and their art. Systems thinking about artists allows an escape from the constraint of talking about what is in and what is out, what counts and what does not, rather than about the larger system, in which culture is seen as a dynamic.

Regarding practice as a system means it is possible to use the notion of 'phase space' as a method of categorising art practice. The range of possible activities and outcomes within an artist's practice is not infinite. It will lie within a range intuitively identified by him or her as possibilities within their chosen context. In that sense, an art practice can be considered in terms of ‘non-linear dynamics’ within a 'phase space'. Artists could be said to develop their practice by the way they construct (or ‘evolve’?) their particular ‘phase space’ by defining it’s boundaries and thus creating their own ‘eco-system’ to facilitate it. Henri Poincaré, who developed the notion of 'phase space' as part of his work on the modern qualitative theory of dynamical systems talked about analysis situs - the analysis of position. Artists ‘position’ their practice within specific contexts – abstract art, for instance, or portraiture. Reacting to an artist’s practice inevitably involves contextualisation to some degree – comparing it with other art like it, or not like it; setting out to understand where it might fit in the art scheme of things. And phase space, it has been said, is is a formalisation of the notion of context.

These notions converge with Dahl’s academic work, where he explores the idea of culture as a complex adaptive system; enabling humans to evolve culturally rather than biologically; conceptually rather than physically.

A phase space for aleatory art work?

Within what sort of ‘phase space’ might these art works be found? If this question is set within dynamical systems terms, it would involve the notion of ‘attractors’. An attractor, in general, is a region of phase space that ‘attracts’ all nearby poinbts as time passes (in the sense that they are naturally drawn towards it). If a dynamical system is watched, it will end up being an attractor after a while.

Attractors are emergent phenomena in dynamical systems. States do not end up on an attractor because they know in advance that that is where they will end up. Dynamical systems are not goal-orientated. (Whether any worthwhile art is actually goal-oriented: whether it knows where its going to get to before it gets there is an interesting question.) But art that is not planned with predictable, intentional outcomes will fit in the phase space for this ‘Chance + Order’ Series, especially work whose production involves the use of chance. Like living suystems, such work is not designed from the top down, but always seem to emerge from the bottom up, from sets of much simpler systems.

1. Mulgan, Geoff [1997] “Connexity, Responsibility, Freedom, Business and Power in the new century” Vintage p.149

2. “… culture as a dynamic; … Critics, faced with a cultural ‘item’, usually ask, is it good or bad, not what is happening”. Williamson, Judith “There’s More to Culture than Yoghurt” ‘Second Sight’ The Guardian Thursday 7th November 1991.

3. “The geometry iof dynamical systems takes place in a mental space, know as phase space. It’s very different from ordinary physical space. Phase space contains not just what happens but what might happen under different circumstances. It is a space of the possible. … The scientific understanding of what actually occurs is based upon the contemplation of possibilities that don’t. Phase space must contain all possible questions, not just the final answers”. Cohen, Jack & Stewart, Ian [1995] “The Collapse opf Chaos. Discovering Simplicity in a Complex World” Penguin Books pp.200 - 203

4. “ … a lot of messy, complicated systems could be described by a powerful theory known as ‘non-linear dynamics’ … the whole really can be greater than the sum of its parts. [-] … nature is not linear”. Mitchell Waldrop, M [1994] “Complexity. The Emerging Science at the Edge of Order and Chaos” Penguin Books p.22 & pp.64/65

5. “Phase space includes not just the actual values of the state variables, but all the potential values. It is a formalisation of the notion of context” Cohen, Jack & Stewart, Ian [1997] “Figments of Reality: the evolution of the curious mind”. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press p.49

6. Cohen, Jack & Stewart, Ian [1995] “The Collapse of Chaos. Discovering Simplicity in a Complex World” Penguin Books pp.205 & 207

7. Mitchell Waldrop, M [1994] “Complexity. The Emerging Science at the Edge of Order and Chaos” Penguin Books p.278

Dahl explores the idea of culture as a complex adaptive system; enabling humans to evolve culturally rather than biologically; conceptually rather than physically.